Stories of witchcraft on the North York Moors have been told for hundreds of years and are rooted in our collection. We have been entertaining visitors with our Ryedale ‘witch’ for decades.

When Museum Founder Bert Frank and his volunteers had finished reconstructing the first domestic or vernacular building, the cottage Stang End, they set to work using the remaining building material to make the ‘Witch’s Hovel’.

Within the Witch’s Hovel, by Angela Waites Photography

There are many stories that they must have had in mind as inspiration. Lots of stories of so-called ‘witches’ can be found around the North York Moors.

Witchcraft within the collection

Within the Museum collection, three spell tokens date from the early and mid-eighteenth century. We interpret them as love charms because they are adorned with hearts, initials and dates. They probably emerge from a particular tradition of female ritualistic magic. At a time when a woman’s expected role was to get married and have children, they must have been purchased in desperation by lone females keen to make a match.

Though ‘witches’ could be male or female, in reality across Europe the vast majority of accusations and persecutions were of women. In this country, approximately eighty percent of those accused were female. Our ancestors turned to the figure of the ‘witch’ to explain what was happening within the community, for example the illness of an animal, milk that wouldn’t churn into butter or a hailstorm that destroyed crops.

Folk stories from the moorland villages tell of the actions of a range of women, like Nanny Pierson. Pierson was a common surname in these parts, so that there have actually been three Piersons connected with witchcraft at various times: a mother and daughter from Goathland, and woman from Rosedale.

Troubling accusations

According to stories, it was the eldest Pierson ‘witch’ in Goathland who was most feared, accused of being able to cripple an unborn child. Old Mother Migg, from Cropton, was also reported to have attracted so many victims into her hovel that she was tossed into a ‘slag of migg’ – migg being manure – and the smell had the effect of discouraging anyone who might have come under her influence.

Nowadays, historians and scholars no longer accept that maleficent magic took place. This means that we no longer believe that these so-called ‘witches’ harmed other people through their spells or curses. For us, therefore, stories of persecution and accusation can be deeply troubling, particularly now that we are able to explain vastly more through science. We aim to share this history during event days at the Museum when our ‘witch’ is often at her ‘hovel’. A volunteer has been taking on this role since the very early days of the Museum’s opening, starting with Edith Butler in the 1960s.

Curious and rare ‘witch posts’

Ryedale Folk Museum also has three unusual wooden posts in the collection, known as ‘witch posts’. One of these can be found within the cottage next door to the hovel, the seventeenth-century Stang End. This ‘witch post’ or ‘heck post’ is actually very rare. These posts are strongly associated with the region of the North York Moors, where the majority have been identified.

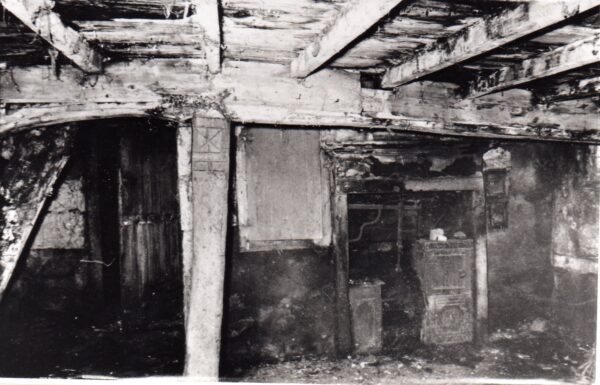

A glimpse inside Stang End, with the post in situ, before it moved to the Museum in 1967

But what are they? The carved oak posts are so-named based on apotropaic (protective) markings, supposedly having the power to prevent evil. This includes a saltire, the carved X-shaped St Andrew’s cross.

Many of use are familiar with superstitions surrounding the impulse to cross – we still cross our fingers for good luck. Hot-cross buns are nowadays marked with an X for tradition’s sake, but once upon a time that too was for protection.

The Witch Post today, by Angela Waites Photography

Magical thinking in the past

Apotropaic markings help us to learn about the beliefs and fears that were once widespread, particularly between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. It was not unusual for protective marks to be placed near doors, windows and chimneys – near any openings to the world from the home.

Our ‘witch posts’ were positioned near the fireplace and so it’s likely that they were believed to prevent evil from entering through the chimney.

In 1597 an influential text was written by King James I. His Daemonologie was a treatise on necromancy, magic and the occult. It was here that King James outlined the importance of protecting the hearth from witches’ familiars, claiming: ‘they will come and pierce through, whatever house or church, though all ordinary passages be closed’, specifically gaining access through any opening ‘the air may enter in at’.

The post in Stang End also contains objects, secreted in the dowel holes, including a silver threepenny bit. One story tells that when the cream was ‘witched’ and wouldn’t churn into butter, the threepenny bit should be carefully dug out from its hiding place and dropped in the pail.

Witch Post Hunt

We are always interested in hearing from people who think they have a witch post in their home or have seen one in the past. It is often said that there are only 20 known about with only two outside of the North York Moors. We are already aware that there are at least two in the Yorkshire Dales and we expect there to be more.

We are asking for the public to help us with our witch post hunt. Finding more of these curious posts might help us to understand their purpose better. If you think you have a witch post or have seen one please contact the Museum – [email protected] – 01751 417367